When the Supreme Court Diverges from Public Opinion

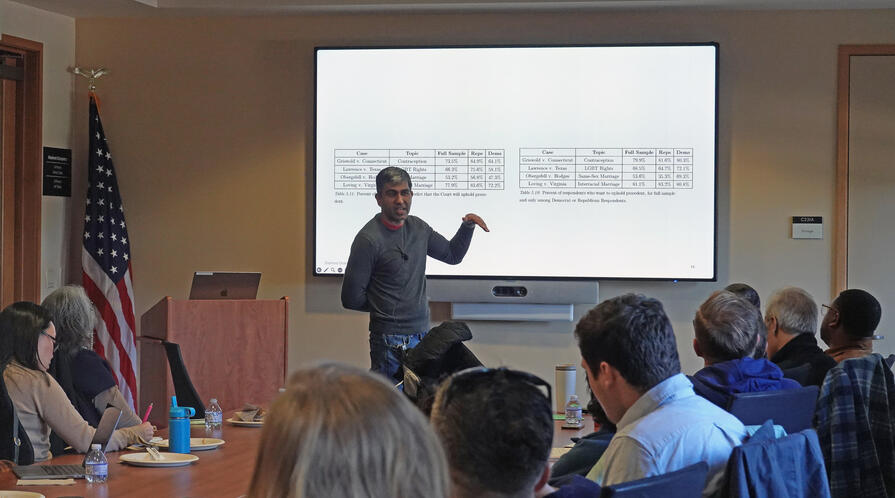

In a CDDRL research seminar held on January 8, 2026, Neil Malhotra, Professor of Political Economy at Stanford Graduate School of Business and courtesy professor of political science, presented his upcoming book Majority Opinions: The Political Consequences of an Out of Step Supreme Court, co-authored with Stephen Jessee and Maya Sen. The project examines how the Supreme Court’s alignment with public opinion shapes its legitimacy, approval, and vulnerability to reform. Malhotra emphasized that the book does not make normative claims about whether the Supreme Court should reflect public opinion but rather offers a positive political science account of how closely the Court tracks public preferences and how that distance shapes legitimacy, approval, and political response.

As discussed by Malhotra, this project began as a result of changes in survey research methodology, shifting from face-to-face and telephone surveys to large-scale internet-based data collection. While these advances were used to study public opinion with respect to Congress and the President, there was a clear gap in applying this approach to the Supreme Court. Hence, starting in 2020, his team partnered with YouGov to conduct annual surveys each spring, prior to Supreme Court decisions, asking respondents how they would rule on major cases scheduled for that term. Respondents were also asked to predict how they believed the Court would decide.

To analyze these responses, Malhotra employs ideal point estimation, mapping respondents, partisan groups, and the Court itself onto a liberal-conservative scale. The data showed that the Court was closely aligned with the median voter in 2020, but its ideological position shifted to the right following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her replacement by Amy Coney Barrett. But in later years, the Court shifted back to the middle following public backlash.

As Malhotra highlighted, rather than asking about constitutional law and legal reasoning, respondents were presented with the policy consequences of cases. For example, in the Bostock case, participants were asked whether it should be legal or illegal for employees to be fired based on sexual orientation, followed by a question asking how they believed the Supreme Court would rule. The data revealed substantial variation across cases. Some issues showed clear partisan polarization, while others reflected broad agreement across parties.

The presentation then turned to public perceptions of the Court. Malhotra showed that respondents are generally poor at predicting Supreme Court outcomes, correctly guessing decisions only slightly more than half the time. This pattern is explained largely by projection, as individuals tend to assume the Court will rule in line with their own preferences. Because the Court has recently leaned conservative, this projection makes Republicans appear more accurate than Democrats.

Finally, Malhotra distinguished between approval and legitimacy, emphasizing the importance of separating the two concepts. Approval reflects short-term evaluations of the Court’s performance and is highly responsive to disagreement with Court decisions. By contrast, legitimacy deals with the public’s belief in the Court’s rightful role as an institution and proves more stable, though still negatively affected when the Court consistently differs from public opinion. As discussed, this difference matters because declining legitimacy can give political elites room to challenge compliance with Court rulings, threatening the rule of law.

Malhotra concluded by situating the project within a broader historical perspective. The book examines moments when the Supreme Court faced severe backlash and subsequently moderated its behavior, including resistance following Brown v. Board of Education. These cases illustrate how threats to enforcement and public acceptance can shape judicial decision-making over time, depicting the political consequences of a Court that moves out of step with the public.

Read More

The GSB's Neil Malhotra examines how ideological distance from voters shapes approval, legitimacy, and political response.