A Dangerous Dilemma for Strong Oppositions Under Authoritarianism

Introduction and Argument:

Many authoritarian countries hold elections where the incumbent might lose. The odds tend to be quite narrow, however, owing to the autocrat’s asymmetric control over economic resources, security forces, media, and so on. An important practical and theoretical question, then, is how the opposition can beat these narrow odds.

Some scholars have argued that oppositions can defeat authoritarian incumbents by building broad, multiparty coalitions. Doing so should not only decrease the autocrat’s vote share but should also deter him from deploying state repression against the opposition’s supporters. Indeed, security forces will struggle or be hesitant to shoot at such large numbers of people, and doing so will likely attract international condemnation. All of this sounds intuitively plausible.

In “When you come at the king,” Oren Samet shows how arguments for building big coalitions overlook a crucial possibility: If the opposition unites and performs well but still fails to defeat the autocrat, he may be “spooked” and react by doubling down on repression. This is because elections provide the government with information about its own and the opposition’s popularity. Too much opposition success further decreases the autocrat’s willingness to tolerate popular elections and freedoms. Therefore, the same strategy enabling oppositions to achieve a “stunning election” can — if the coalition fails to take power — lead to a “nearly stunning” election that further entrenches authoritarianism. Hence the paper’s title, a quote from The Wire’s Omar Little: when “you come at the king, you best not miss.”

The paper provides both cross-national data and an in-depth case study of Cambodia to show how the logic of nearly stunning elections poses a serious dilemma for democracy promoters: When oppositions cannot defeat autocrats, then they must achieve a “sweet spot” of neither too many votes (which scares the incumbent into autocratizing) nor too few (which fails to threaten the incumbent and compel him to make democratic concessions). Yet deliberately planning to hit this sweet spot is simply not possible. Samet thus offers an important challenge to the claim that bigger is better in authoritarian elections.

Cross-National Findings:

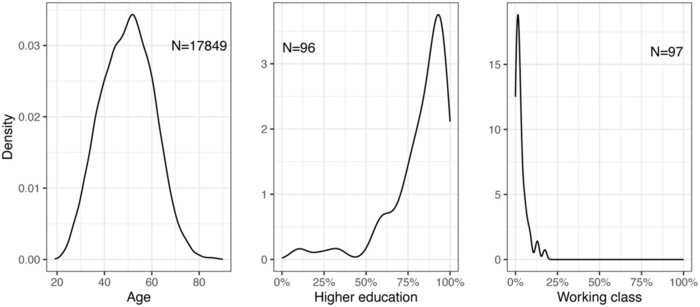

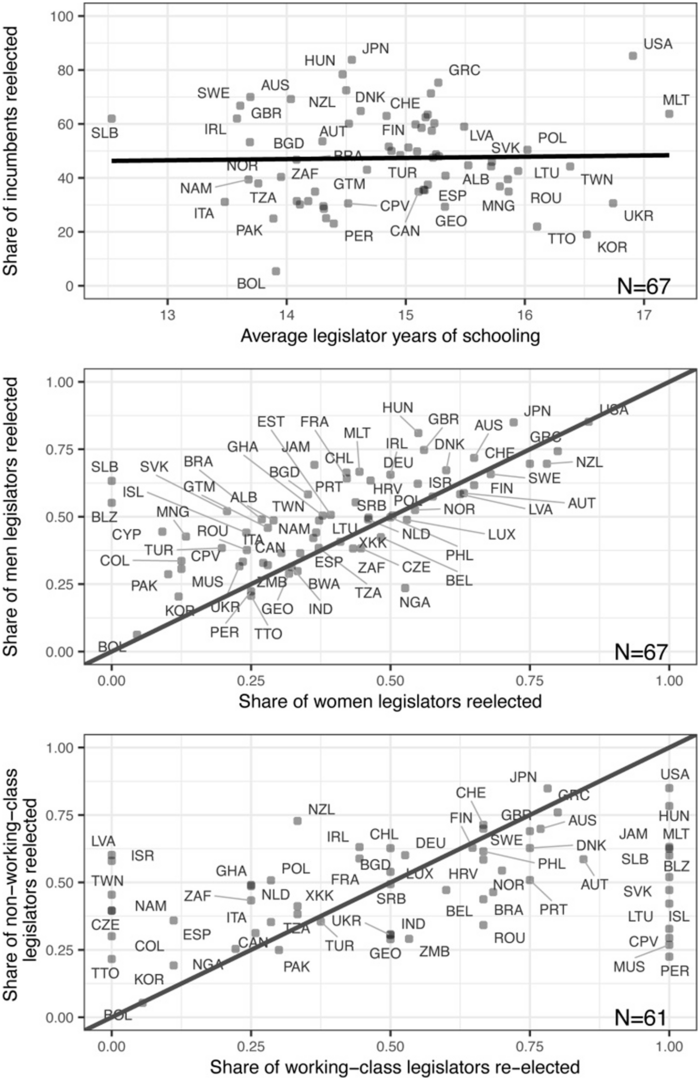

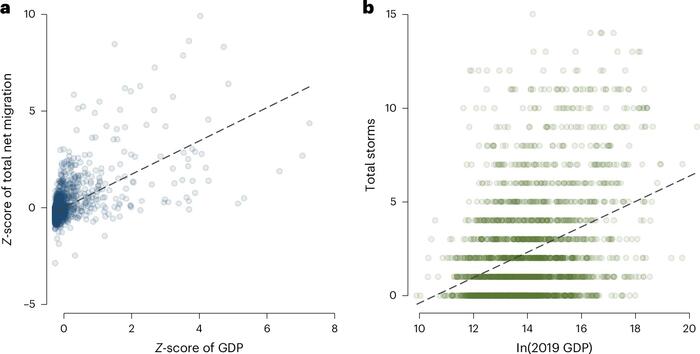

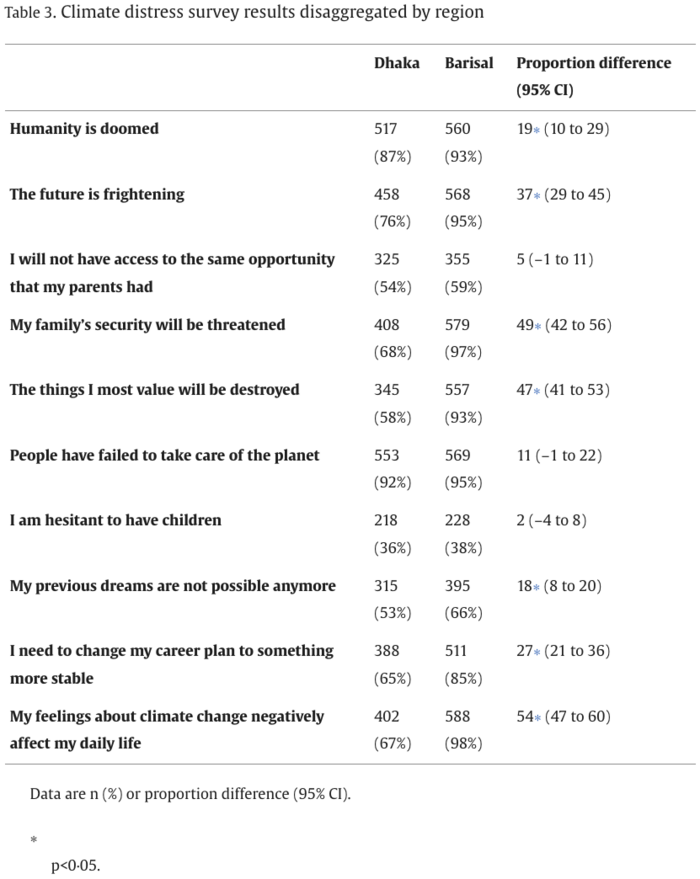

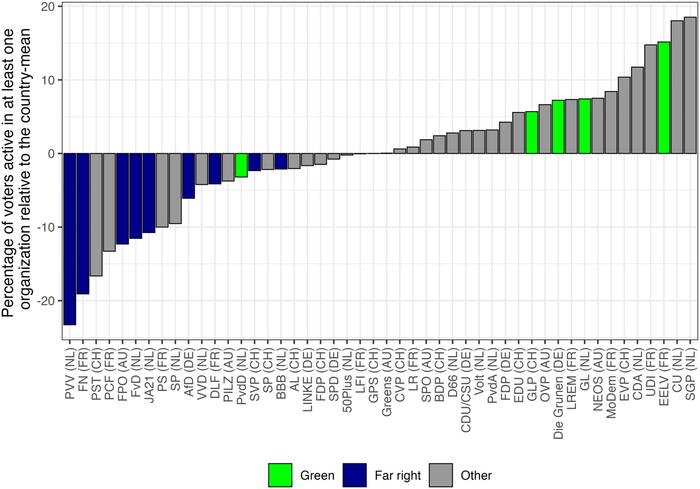

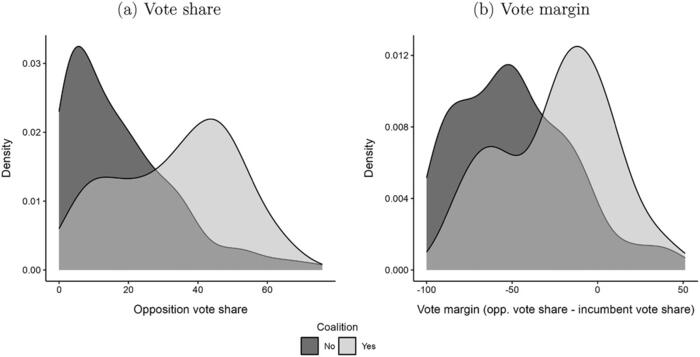

Samet’s argument about the pitfalls of nearly stunning elections implies three hypotheses. First, and as previous scholarship suggests, coalitions should outperform individual opposition parties in authoritarian elections. Second, absent the incumbent’s defeat, autocratization is more likely as the opposition’s vote share increases. And third, absent the incumbent’s defeat, countries with high-performing oppositions should witness (a) an increase in state repression and (b) decreases in the quality of elections in the years following a nearly stunning election. Samet then analyzes all elections from 1990 to 2022 in cases where the same authoritarian leader or party had ruled for at least 10 years. This yields 286 elections: 58 (20%) featured coalitions, and 28 (10%) featured electoral turnovers. These numbers alone paint a bleak picture of the prospects for beating dictators.

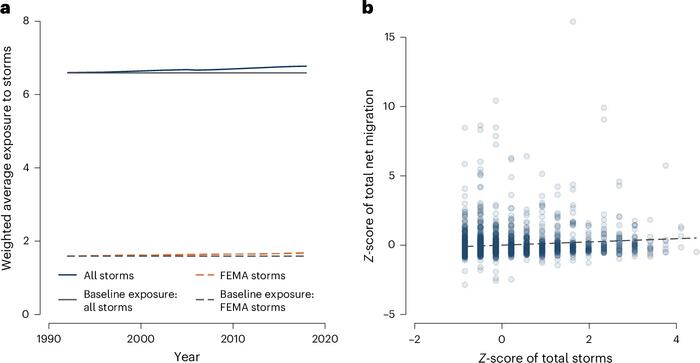

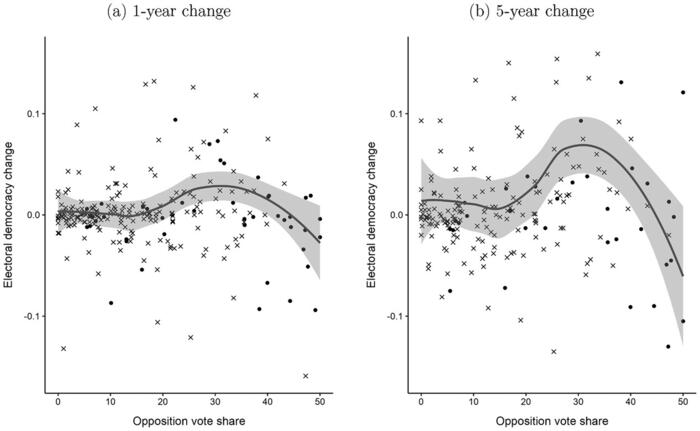

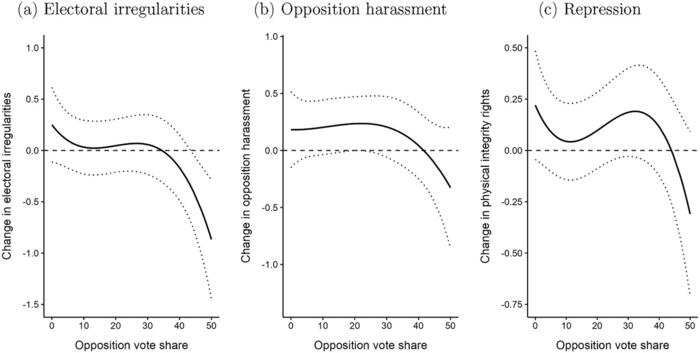

The statistical results broadly support Samet’s hypotheses. Coalitions do in fact perform better at the ballot box, winning a median vote share of 36% (compared to just 13% for individual parties). In addition, and consistent with the idea that hitting the “sweet spot” will encourage autocrats to make concessions, Samet finds a positive association between moderately strong opposition performance and democratic change. Importantly, however, levels of democracy decline sharply as the opposition vote share approaches 50%. Nearly stunning elections thus appear to provoke autocratization, both in the short- and medium-term. Finally, the relationship between nearly stunning elections and repression or electoral fraud is somewhat weaker. This may be because the autocrat has more than just these two tools at his disposal — he might limit the number of seats that can be contested in future elections, prevent the opposition from accessing state media, and so on.

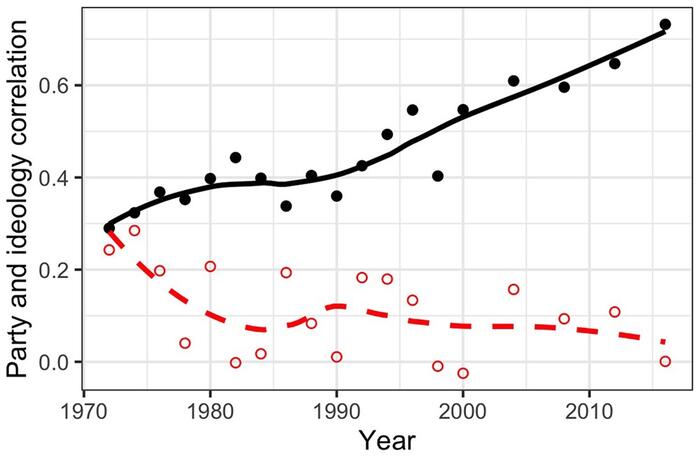

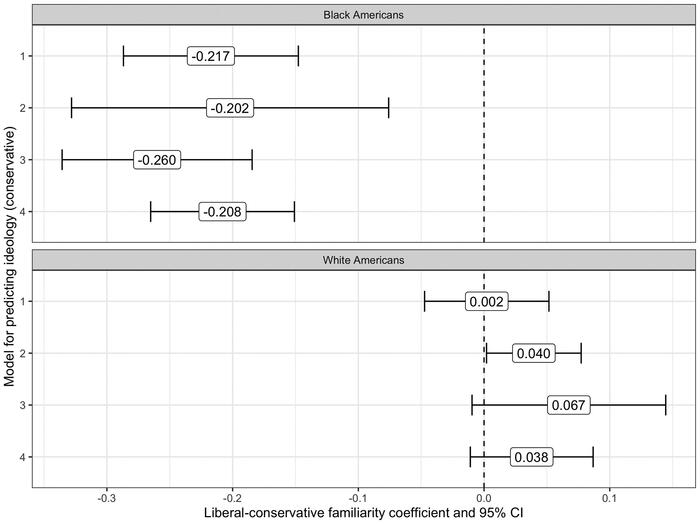

FIGURE 2: Opposition performance in authoritarian elections. Note: Density plots display the frequency of specific opposition (opp.) vote shares (left) and vote margins (right) broken down by coalition status.

FIGURE 3: Opposition performance and electoral democracy change. Note: Displays elections that did not feature turnovers, plotted along two dimensions: opposition vote share and change in electoral democracy. ∙ (dot) denotes election with coalitions; × denotes election without. The gray lines plot LOESS regressions fit to the data, with gray shading indicating 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 6: Predicted change in repression and electoral manipulation, with controls. Note: Displays predicted post-election changes in (1) V-Dem measure of electoral irregularities, comparing election at t with election at t + 1; (2) V-Dem measure of government intimidation of opposition, comparing election at t with election at t + 1; (3) Fariss (2014) physical integrity rights measure 3 years after election, using the lagged score as a baseline. Includes all elections that did not result in turnovers. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The Cambodia Case:

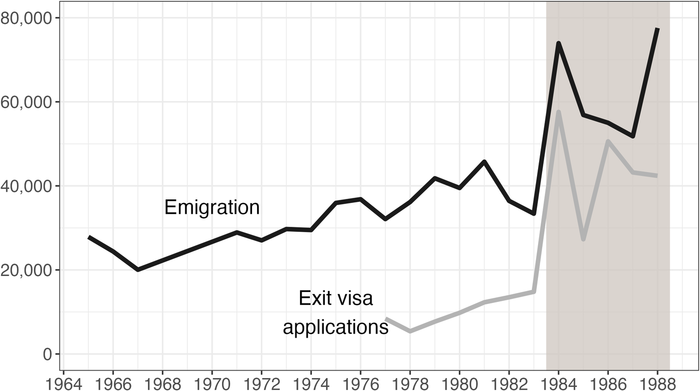

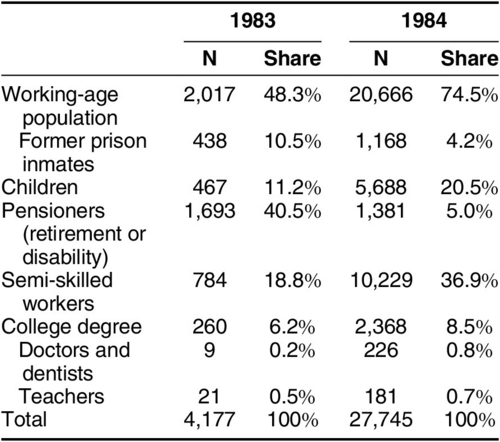

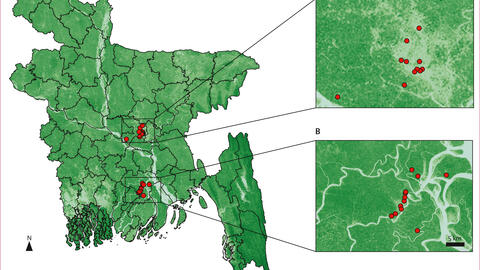

Samet concludes by showing how his theoretical process — oppositions uniting, nearly winning an election, frightening the incumbent, then increasing authoritarianism — is borne out in Cambodia’s recent political history. Throughout the 2000s, Cambodia’s opposition was fragmented, in part due to deliberate actions by its authoritarian Prime Minister, Hun Sen. Ahead of the 2013 elections, in the face of mounting popular dissatisfaction with the government, the two largest opposition parties coalesced. Hun Sen was confident in his position, in part because Cambodia’s strongest opposition party had won just 22% of the vote in 2008. As such, he pardoned Sam Rainsy, one of the country’s most prominent opposition leaders, whom he invited to return from exile.

The coalition did remarkably well in 2013, winning around 45% of the vote, but then alleged fraud and refused to take their seats in parliament. Opposition supporters then took to the streets in protest, where they were met with state violence. Yet Hun Sen made a number of concessions to successfully quell the protest crisis, including reforming the election commission.

By 2015, however, signs of autocratization became glaring. Opposition lawmakers were publicly beaten by the personal bodyguards of Hun Sen, who withdrew his prior pardon of Rainsy. Other opposition leaders faced politically motivated legal cases. Ahead of the 2018 elections, Hun Sen’s government hired an external survey firm, which found the opposition had become even more popular among Cambodians since 2013. Hun Sen’s fears were aggravated by a strong opposition performance in the 2017 local elections.

Samet argues that this was the last straw: the government responded by promptly arresting and exiling opposition leaders and dissolving their coalition. All of this constituted the most dramatic instance of autocratization in Cambodia since the 1990s. Hun Sen’s allies then ran unopposed in the 2018 elections. By this time, the opposition was once again divided — particularly as regards how to face a government whose elections could barely be characterized as anything other than window-dressing. “When you come at the king” offers an important if distressing lesson for practitioners and scholars of democracy.

*Brief prepared by Adam Fefer

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [3.5-minute read]