The Effects of Financial Exposures on Support for Climate Action

On October 9, 2025, FSI Senior Fellow Saumitra Jha presented his team’s research on how exposure to financial markets — meaning individuals’ exposure to tailored opportunities to directly engage with investment platforms and decision-making — can increase support for action on climate change. This CDDRL research seminar expanded on Jha’s earlier research on the effects of financial exposure and literacy as tools for reducing political polarization, including studies conducted in Israel, Mexico, and the United Kingdom.

During the seminar, Jha highlighted the study's relevance in an era of democratic backsliding, rising populism on both the right and the left, and increasing economic uncertainty. Jha emphasized that basic financial literacy — the ability to understand and practically apply financial concepts such as saving, investing, and diversifying risks— is essential for citizens navigating this environment. Jha’s team designed interventions that empower citizens, both in rich and poor countries, to build financial knowledge and, by focusing on common investments and the common good, ultimately mitigate political polarization and conflict.

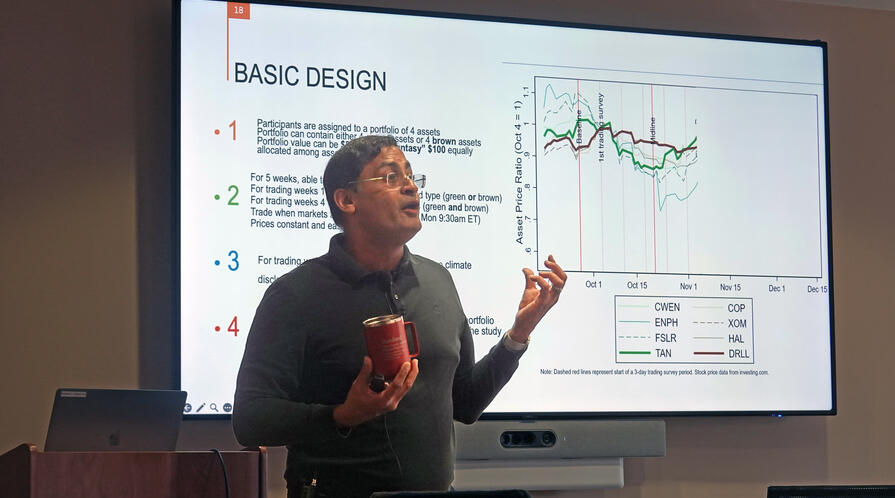

The study focused on the partisan issue of climate change in the United States. Participants were oversampled from states either disproportionately affected by climate change or central to the green-energy transition — Pennsylvania, West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Arizona, Ohio, South Carolina, and Kentucky. Each participant in the treatment group initially received an investment portfolio that tracked stocks from either green energy companies (firms at the forefront of the transition, engaged in renewable energy like solar and wind) or brown energy companies (firms earlier in the transition, engaged in the extraction of fossil fuels such as oil and natural gas). Subjects had $50–$100 of real money or a virtual portfolio of funds to invest.

For five weeks, participants used a Robinhood-style investment platform (a simple online interface for buying and selling stocks) to trade their stocks. Midway through the study, they were able to trade across both green and brown stocks. At this point, they received additional financial disclosures (basic company performance data) and had access to climate-impact disclosures (data on companies' greenhouse gas emissions and how they affect or are affected by climate change). However, this is currently a central policy debate; very few participants actually chose to review climate disclosures, which Jha identified as a research question for a companion paper. The research team then evaluated results in four categories: (1) beliefs about human agency and tradeoffs with the green energy transition, (2) policy preferences, (3) political attitudes, and (4) personal behaviors.

The data demonstrated that this financial exposure treatment — i.e., hands-on stock trading experience — had a significant, meaningful, and lasting influence on participants’ beliefs. Relative to control, treated participants were 9% more likely to agree or strongly agree that human activity is a significant contributor to climate change. They further became more supportive of both government and corporate action to mitigate climate change, and came to view the green-energy transition as potentially economically beneficial.

Further, the intervention was empowering, raising the financial literacy of participants and increasing their ongoing consumption of financial news outlets, rather than social media or Fox News. These effects were observable even eight months after the study.

Further, these changes were not preaching to the choir — instead, the effects were observed across the political spectrum, particularly among those who were ex ante climate change skeptics. However, while treated participants were more likely to donate to climate causes and to consider climate when investing and working, they did not report an overall increased willingness to change their daily lives. For example, while reporting an increased willingness to reuse recyclable bags, most did not report an increased willingness to change ingrained daily habits, such as eating less meat or changing commute patterns.

Jha also previewed new results from a companion paper based on a long-term survey conducted 8 months after treatment. To examine how the treatment changes how participants preferred climate action to be implemented, the research team gauged support for two approaches: the “Abundance approach”, popularized by Ezra Klein, and the “Conservation and Regulation approach.” The Abundance approach emphasizes expanding investments in clean energy infrastructure, sustainable housing, and economic growth as solutions to climate change. By contrast, the Conservation and Regulation approach focuses on reducing energy use through government regulation, strong local autonomy, and personal restraint. The financial exposure treatment significantly raised the share of subjects supporting the Abundance approach.

Read More

Can financial literacy shape climate beliefs? Saumitra Jha’s latest study suggests it can — and across party lines.