Meet Our Researchers: Professor Michael McFaul

The "Meet Our Researchers" series showcases the incredible scholars at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL). Through engaging interviews conducted by our undergraduate research assistants, we explore the journeys, passions, and insights of CDDRL’s faculty and researchers.

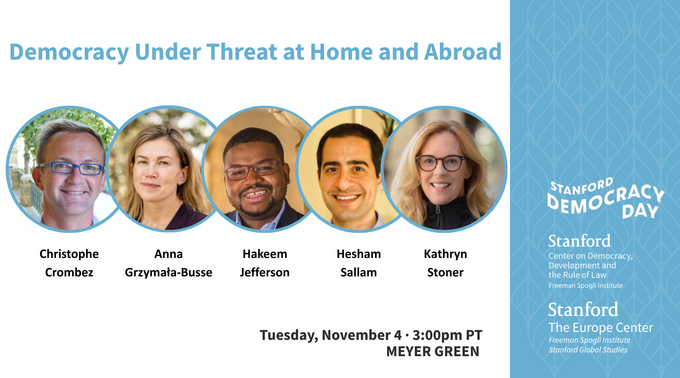

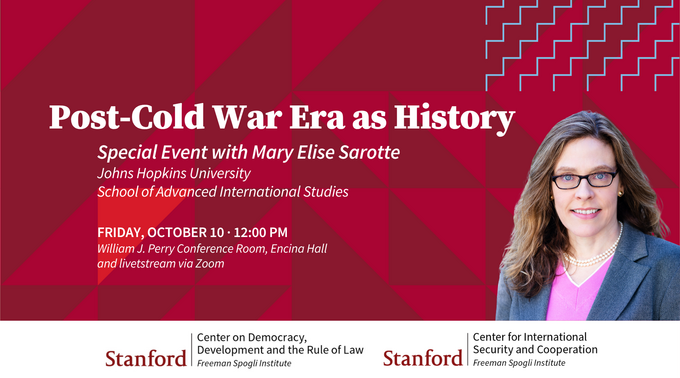

On a busy Thursday afternoon at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), I sat down with Professor Michael McFaul, Director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) and Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Professor of International Studies in the Department of Political Science, for a wide-ranging conversation on great power competition, U.S.–China relations, Cold War legacies, and the role of ideology in shaping global politics.

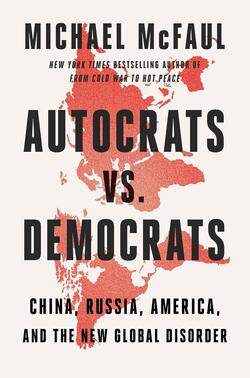

A former U.S. Ambassador to Russia and one of the most prominent voices on American foreign policy, Professor McFaul’s new book Autocrats vs. Democrats: China, Russia, America, and the New Global Disorder examines the stakes of the current geopolitical moment. Over the course of nearly an hour, we spoke about the elasticity of the term “great power competition,” the dangers of isolationism, the importance of middle powers, and the enduring influence of ideas in world politics. He also shared advice for young people interested in foreign policy, as well as the two books that shaped his early intellectual journey.

The term “great power competition” has become such a potent buzzword in Washington. Everyone uses it all the time, and it feels like it can mean many different things depending on who’s talking. How do you define great power competition? And do you think there’s a way for Washington to stop treating it as a catch-all phrase and instead turn it into a strategy with clear ends, means, and metrics?

The original motivation for writing my book came in 2017 when the Trump administration came into power. They wrote a National Security Strategy that very explicitly stated that we were in a new era of great power competition. And that document, in my view, became one of the most famous national security strategies of recent decades because it was so clear about that shift. The Pentagon even came up with an acronym — GPC (great power competition) — and when they create an acronym, it usually means it’s here to stay.

Around that time, there was also a big debate about whether we had entered a new Cold War. It began first with Russia — books were being written about a “new Cold War” as early as 2009 — and then the conversation shifted to China. So my first motivation for writing the book was to ask: Is this actually true? Is the Cold War analogy useful or not? My answer is complicated. Some things are similar, some things are different. Some of what’s similar is dangerous; some isn’t. Some of what’s different makes things less dangerous, and some of what’s different is scarier than the Cold War. If we don’t get the diagnosis right, then we won’t have smart policies to sustain American national interests.

You’ve written and spoken about how the Cold War analogy can be misleading. What are the main lessons from that period that we should remember, both the mistakes and the successes?

Because we “won” the Cold War, a lot of the mistakes made during it are forgotten. I use the analogy of when I used to coach third-grade basketball. If we won the game, nobody remembered the mistakes made in the first quarter. But if we lost, they remembered every single one. Because the U.S. “won,” people forget the mistakes.

There were major errors: McCarthyism, the Vietnam War, and allying with autocratic regimes like apartheid South Africa when we didn’t have to. So, in the book, I dedicate one chapter to the mistakes we should avoid, one to the successes we should replicate, and one to the new issues the Cold War analogy doesn’t answer at all. It’s not about glorifying the past; it’s about learning from it in a clear-eyed way.

President Trump and former President Biden have had very different approaches to great power competition. President Biden’s vision is closer to a liberal international order, whereas President Trump talks about a concert of great powers — almost a 19th-century idea. How do you evaluate that model? Do you think it can work today?

The short answer is no. I don’t believe in the concert model or in spheres of influence. That’s the 19th century, and this is the 21st. Trump’s team itself was internally confused on China. Trump personally thinks in terms of great powers carving up the world into spheres, but the national security strategy he signed was written by his advisors, not necessarily by him.

In thinking about Trump, I find it useful to remember that U.S. foreign policy debates don’t fall neatly between Democrats and Republicans. They run along three axes: isolationism versus internationalism, unilateralism versus multilateralism, and realism versus liberalism. Trump is radical on all three fronts — he’s an isolationist, he prefers unilateralism, and he doesn’t care about regime type. I think that combination is dangerous for America’s long-term interests.

What role do middle or “auxiliary” powers — like India, Brazil, or Turkey — play in this evolving landscape of great power competition?

This is one of the biggest differences between today and the Cold War. Back then, the system was much more binary. Today, the world is more fragmented. I think of it as a race: the U.S. is ahead, China is closing the gap, and everyone else is running behind. But they’re running. They have agency. They’re not just sitting on the sidelines.

Countries like India, South Africa, Turkey, and Brazil are swing states. They’re not going to line up neatly with Washington or Beijing. BRICS is a perfect example — democracies and autocracies working in the same grouping. The U.S. has to get used to living with that uncertainty. We need to engage, not withdraw.

And at the same time, while the U.S. seems to be retreating from some of its instruments of influence, China appears to be expanding. What worries you about this divergence?

It’s striking. We’re cutting back on USAID, pulling out of multilateral institutions, shutting down things like Voice of America, Radio Free Asia, Radio Free Europe, and cutting back on diplomats. Meanwhile, the Chinese are expanding their presence, their multilateral influence, their media footprint, and their diplomacy.

If the autocrats are organized, the democrats have to be organized too. We can’t just step back and assume things will turn out fine. That’s not how competition works.

During the Cold War, despite intense rivalry, the U.S. and USSR cooperated on nuclear nonproliferation and arms control. How do you see cooperation taking shape in today’s U.S.–China rivalry?

That’s a really important point. Cooperation in the Cold War wasn’t just about deterring the Soviets — it was also about working with them when we had overlapping interests. The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty of 1968 was a monumental achievement. It was signed at the height of the Vietnam War, while we were literally fighting proxy conflicts, and yet we found common ground on nuclear weapons.

I think something similar can and should happen now. Even if we’re competing with China, and even with Russia, there are areas where cooperation is in everyone’s interest: nuclear arms control, nonproliferation of dangerous technologies like AI and bioweapons, and climate change. These are existential issues. We cooperated with our adversaries in the past; we should be able to do it again.

One of the big debates in international relations is about the role of ideology. How much does ideology matter in this current geopolitical context?

It matters a lot. My book isn’t called Great Powers — it’s called Autocrats vs. Democrats for a reason. I believe ideas and regime type shape international politics.

Putinism and Xi Jinping Thought are exported differently. Putinism — illiberal nationalism — has ideological allies in Europe and here in the U.S. Xi’s model is more economically attractive to parts of the Global South. Power matters, of course, but it’s not the only thing.

You can see this clearly if you compare Obama and Trump. There was no big structural power shift between 2016 and 2017, but their worldviews were radically different. That’s evidence that ideas and individuals matter a great deal in shaping foreign policy.

You’ve warned about the dangers of U.S. retrenchment. Are there historical moments that you see as parallels to today?

I worry about a repeat of the 1930s. When Italy invaded Ethiopia, Americans said, “Where’s Ethiopia?” When Japan invaded China, they said, “Why do we care?” Then came 1939. Stalin and Hitler invaded Poland, and we still said, “That’s not our problem.” Eventually, it became our problem.

If we disengage now, we may find ourselves facing similar consequences. That’s part of why I wrote this book — to push back against the idea that retrenchment is safe. It’s not.

To close, what advice would you give to students who want to build careers like yours? And, could you recommend a book or two for young people entering this field?

Be more intentional than I was. Focus on what you want to do, not just what you want to be. Develop your ideas first, then go into government or academia to act on them. Don’t go into public service just for a title. I saw too many people in government who were there just to “be” something, without a clear agenda. The “to do” should come first; the “to be” comes later.

As for books, my own book, Autocrats vs. Democrats: China, Russia, America, and the New Global Disorder, is coming out soon — you can pre-order it. But the two books that shaped me the most when I was young are Crane Brinton’s The Anatomy of Revolution and Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe Schmitter’s Transitions from Authoritarian Rule.

Read More

Exploring great power competition, Cold War lessons, and the future of U.S. foreign policy with FSI Director and former U.S. Ambassador Michael McFaul.