TRANSCRIPT

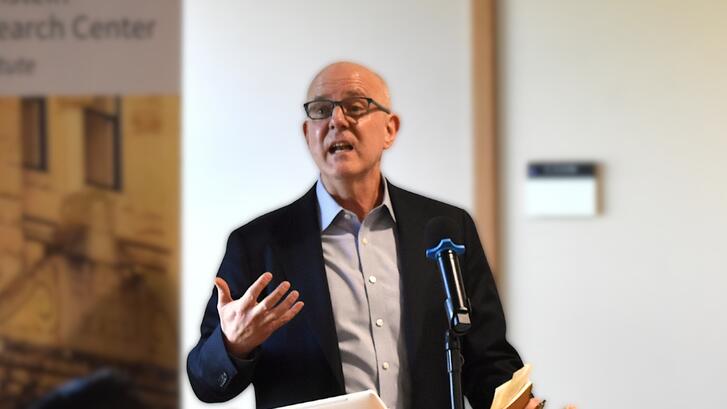

McFaul: Hey everyone, you're listening to World Class from the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanfo rd University. I'm your host, or maybe I should say I'm your co-host, or maybe I should say this is the last time I'll be hosting World Class from Stanford University. Because as listeners and followers of FSI’s news may know, after eleven years, I just stepped down as the director a few weeks ago and I've handed the baton to my guest today, Colin Kahl, who's the brand new director of the Freeman Spogli Institute.

And it is fantastic, Colin, that you agreed to take on this assignment. This is another form, I consider, of public service just like what you've done for the U.S. government and the United States of America.

Colin, as you're going to hear in a few minutes, is the perfect mix of scholar and practitioner that we so value here at FSI. And we are really lucky that you are taking up this assignment.

So Colin, welcome to World Class where everybody will be listening to you forthcoming for, I hope, many, many years.

Kahl: Thanks Mike, it's a real pleasure to be with you and most especially thank you for your tremendous decade plus—eleven years—of service to FSI and the Stanford community. And I look forward to continuing to work with you as you transition to the next thing. And we should talk about that too. But it's great to be on the pod with you.

McFaul: Glad to be here. And just so everybody knows, I stepped down from FSI, but I'm not retiring from Stanford. I still have my various day jobs here. We can come back to that a little bit later.

But Colin, why don't you just tell our listeners and our viewers a little bit about your road to this present position.

Kahl: Yeah, sure. So I grew up in the Bay Area. I grew up in the East Bay in Richmond, California. I applied to Stanford as an undergrad, didn't get in. Applied again as a graduate student, didn't get in. So I got educated elsewhere. I went to the University of Michigan, which is a great school.

McFaul: Very fine institution.

Kahl: And then I went to Columbia University where I got my PhD in political science, focused on international relations and conflict studies. I did my PhD work in the 90s when the field of international relations was trying to figure out what the field even meant after the end of the Cold War.

So it was an exciting and very kind of plastic moment to be doing scholarly work.

I then started my first teaching job at the University of Minnesota in 2000. And of course, a year after that, 9/11 happened. And it was a terrible event for the United States and for the world. For those of us who lived in New York City—I did my graduate work there—it was especially painful.

And it really drove me to want to figure out a way to both do the academic side of understanding the world, but also see if there was a way to engage in public service. So my fifth year at the University of Minnesota, I actually got a fellowship through the Council on Foreign Relations . . .

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: . . . that put me at the Pentagon for a year and a half. This was during the George W. Bush administration. Don Rumsfeld was still the Secretary of Defense. I worked there for a year and a half. I kind of caught the bug, the Washington bug.

McFaul: What was your portfolio back then, Colin? Just remind everybody.

Kahl: So I worked in a small office called the Stability Operations Office. It was only 24 of us. worked within the office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy. It had historically been called the Peacekeeping and Humanitarian Affairs Office

McFaul: Right, right, I remember that. They changed it, right.

Kahl: But Rumsfeld was not a fan of peacekeeping, so they changed it to ‘stability operations.’

But at the time, most of what our office did was try to help the U.S. military reform itself in the face of the struggles that the U.S. military was facing in Iraq and Afghanistan with the stabilization missions there.

There's a lot of dark humor at the Pentagon, but we sometimes joked that the 24 of us were doing stability operations while the other 24,000 people in the building were doing instability operations.

McFaul: [laughing] Instability operations, yeah, that’s right.

Kahl: But anyway, it was totally exciting. You know, we were there when when U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine was being revised and a bunch of other things.

So that was 2005, 2006. I kind of caught the bug and decided to try to stay in Washington. So I actually took a job at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service where they were kind enough to give me tenure and I taught in the security studies program there for a decade.

McFaul: Let's just . . . hold on, hold on. Let's be clear. They were not ‘kind enough’ to give you tenure; you earned tenure. Nobody gives tenure anywhere. Congratulations that you landed that job.

Kahl: So, I was in the security studies program there for ten years, about a half that time I served in the Obama administration. We served together . . .

McFaul: Together, yes!

Kahl: . . . in the first few years. I was back at the Pentagon as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East during the drawdown of our forces from Iraq during the Arab Spring.

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: During the first flare up of Israel-Iran tensions over Iran's nuclear program. By the way, none of that was my fault, but I was there when all that stuff happened.

And then I went back to Georgetown for a few years and then I got pulled back into the Obama administration at the end to work at the White House as a deputy assistant to the president and as then-vice president Biden's national security advisor. So I was there for Russia's first invasion of Ukraine . . .

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: . . . and the Central American migration crisis and tensions in the South China Sea and the campaign against the Islamic State and the Iran nuclear deal. A lot of interesting things.

And then, when Trump was elected the first time, Mike, you reached out to me with this amazing opportunity at Stanford, the Steven C. Házy Senior Fellow chair that I currently occupy. Applied for the job and got it. It was an opportunity to come back to Stanford. I’ve sat at CISAC, the Center for International Security and Cooperation here at FSI. And I was the co-director of CISAC for a couple of years.

And then last but not least, when Biden was elected president, he asked me to serve as the undersecretary of defense for policy back at DoD, which is essentially the number three civilian and senior policy advisor to the secretary. And I did that for the two first two and a half years of the Biden administration.

Also also very interesting times: fall of Afghanistan . . .

McFaul: Yes.

Kahl: . . . Russia's further invasion of Ukraine, rising tensions with China, dealing with the aftermath of COVID, lot of changes in the world.

So anyway, I'm glad to be back at Stanford. I've been back since the summer of 2023, and I'm excited to try to fill the very big shoes that you've left at FSI after eleven years.

McFaul: Well, let's talk about the future in a minute, but just two follow-up questions on your history. You've had lots of government jobs you just described. I can't think of anybody that's had a more diversified set of experiences in national security. We are lucky to have you here.

Tell us about the best day of any of those jobs and tell us about the worst day and maybe reverse that. Worst day first, best day second.

Kahl: So first of all, I'm fortunate to have had the opportunity to serve my country. I believe in it strongly. I've served in Republican administrations and Democratic administrations. I've worked for two Republican secretaries of defense and two Democratic secretaries of defense. So I think I've demonstrated my nonpartisan bona fides in how I've served my country.

And I just want to mention that because I think it's important.

McFaul: Yes, it is important.

Kahl: Because, of course, FSI is a nonpartisan place.

Worst day and best day: in a sense, it's almost the same. There was no more harrowing experience than the collapse of Kabul.

I was actually at the NIH getting a medical treatment when I got a text message from the secretary's chief of staff that I needed to hurry back to the Pentagon. So I literally pulled an IV out of my arm and raced back to the Pentagon because Kabul fell.

And obviously that was a tremendously terrible event for Afghanistan. It was a particularly harrowing way for the 20-year U.S. involvement in Afghanistan to end. But it also put us on the clock. You know, we had basically 17 days before the deadline for all American forces to be out of Afghanistan, and we suddenly had to do a lot of things.

We had to flood forces back into the country to occupy an airport that was now in hostile Taliban territory when the Taliban took over Kabul. We had to secure that airport. We sent five or six thousand soldiers and Marines to that airfield. We had postured them in the region previously to be able to do that, but we had to get them there.

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: And then we then had to oversee the evacuation of 125,000 human beings in two weeks, which had never happened in human history and no other country in the history of the world would have been capable of doing. And it was pretty horrible.

McFaul: Yeah.

Kahl: A lot of terrible human tragedies. Obviously, we got a lot of people out. A lot of people weren't able to get out. There was the terrible ISIS bombing that killed 13 of our brave service members. Toward the end of the evacuation, there was an errant U.S. strike on what we thought was an ISIS operator that turned out to be an aid worker and his kids. It was horrible.

But I'm also incredibly proud of what we were able to do. I mean, in the macro sense, because we were able to project our power back into Afghanistan, lock down that airfield and get all of those people to safety, including the family members of some Afghans who worked for me. We were able to get a lot of people out.

We were able to bring them to bases and facilities that didn't even exist when the crisis . . . I mean the bases existed, but the facilities to house these people in the Gulf and in Europe and back here in the continental United States . . . the amount of diplomacy that required, the amount of logistics by the U.S. military that it required. It was an unbelievable operation.

And so it was terrible. But it was also an extraordinary demonstration of what the United States was capable of doing even at these dark moments.

McFaul: That's a great way to put it together. I would guess we would not have been able to do that if we did not have NATO allies and bases in that part of the world, or is that incorrect? I don't know the logistics of that part of the world.

Kahl: If anything, it's an understatement. I think one of the things that distinguishes the United States from every other superpower or global power in history is the depth and breadth of our network of allies and partners. At the heart of that are our treaty allies in the NATO alliance, but also in the Indo-Pacific region, so think South Korea, Japan, Australia.

McFaul: All of them, right.

Kahl: But we also have very close security partnerships in the Middle East. And so literally it would not have been possible to fly aircraft into Afghanistan, fly people out from Afghanistan into places like Qatar, Bahrain, UAE, Saudi Arabia. But then we brought them to Germany and Spain and other U.S. bases in Europe. And then we brought them back to bases here in the United States.

And that network, literally that network made it possible. And had we not had those allies and partners when that happened, we couldn't have done what we did. We couldn't have done any of it. We couldn't have gotten any of our people out.

And so that really is like some of the secret sauce to America's power and influence in the world. And it remains the case that we have more allies and partners than any other country in history.

But it's also the case that those alliances and partnerships are probably more strained than they've been in my lifetime.

McFaul: So, one other historical question about you. Why did you come to Stanford? I mean, you've got this great job at Georgetown. You obviously are connected to the policy community. We're far away out here. Tell us about that decision.

Kahl: Part of it is I grew up in the Bay Area. Part of it is that, mean, Georgetown is a remarkable place, but Stanford's one of the two or three best universities in the world. We had a great community of scholars out here. And a lot of the issues that I'm particularly passionate about now—especially the intersection of technology and geopolitics— I mean, this is ground zero for a lot of that.

And so it was for a mix of kind of lifestyle reasons and professional reasons. And it's been awesome.

McFaul: Well, that's a great segue to what I wanted to ask you next, which is about the big agenda items. I mean, FSI has a lot going on: we have lots of centers here, as our listeners know, because we've had many guests from all, I think all of our centers over the time I've been here.

But you've got some particular things that you want to focus on. I know, because I talked to people that were part of the selection committee, that that was what was most impressive about you, is that you have a big agenda. Tell us about that agenda, Colin.

Kahl: As your longtime listeners undoubtedly know, FSI is an interesting place because FSI Central, where you were the director until three weeks ago, and now I sit, essentially sits over nine main research centers that cover everything from democracy to international security to regions like Asia and Europe to issues like technology and defense innovation, food security, global health.

And the breadth of this place is extraordinary. But it's also a highly decentralized place. Yes, we oversee the centers, but in many respects, the centers are kind of quasi-autonomous nation states.

McFaul: Exactly, exactly.

Kahl: So this isn't about trying to micro-manage our centers; that would be a fool's errand. It is actually, though, trying to look for ways to have the whole of FSI add up to more than the sum of its parts. And to look for synergies across our centers on really big questions.

You took the helm of FSI, I believe, back in 2015?

McFaul: Yes.

Kahl: To state the obvious, the world in 2026 is a lot different than it was in 2015. And so, FSI has to adapt to that world. And I think there are four really big questions of the moment that I think FSI really needs to be impactful on.

One is that we're in this new age of geopolitics. And it's become kind of trite to note that, you know, we have a resurgence of great power politics and competition between the United States and China and Russia and other major powers. But it actually runs deeper than that.

The distribution of power in general across the world is fundamentally different than it was 15, 20 years ago, let alone 50 years ago. The United States remains the world's most consequential actor, but China is nipping at our heels as a global superpower. And while Russia can't dominate the world, Russia can blow up the world. And we also know that countries like China, Russia, North Korea, Iran are working more closely together.

At the same time, the traditional role that the United States has played in the world since World War II or since the end of the Cold War is changing. And our relationship with our traditional allies is changing. And I think anybody who kind of paid attention to the World Economic Forum in Davos over the last few days heard speeches from the Prime Minister of Canada referring to the rupture in the international order.

And there's just the sense that things are fundamentally changing. And some of that may be a direct reaction to some of the policies of President Trump. But frankly, I think a lot of it is structural, that the policies of the current administration are as much an artifact as they are a cause even if they are accelerating some of the structural dynamics.

And then of course, there's big chunks of the world that doesn't want to be on anybody's team.

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: That wants to be non-aligned and multi-aligned. A lot of countries in the so-called ‘global south’ fall in that category. So we should be studying this new era of geopolitics

I would encourage you to say more about how you plan to study it, because I know you have a really fascinating project in this space that brings FSI and Hoover scholars together on some of these questions.

Kahl: So, one issue is the new geopolitics. The other though is what I call the new techno politics. It's actually a term I think Ian Bremmer coined.

But it's not just the notion that technologies like AI, biotech, quantum, space, clean energy are transforming our world, but also that the actors at the heart of these innovations are these multinational corporations that if their market cap was translated into GDP,

they would rank as G20 nations, right? When you're Nvidia and you have $5 trillion

McFaul: That's a great point.

Kahl: Like that would be the top half of the G20. But it's not just that. They have global presence. And for a lot of these companies, they have near sovereign control over the environments through which we live our lives.

McFaul: That's a great point.

Kahl: So, think cloud service providers, social media platforms, but also the infrastructure: undersea cables, low earth orbit constellations. And all of these things are under regulated spaces. So, it's not just that the technology is changing the world, but the companies are international actors. And again, where else should we be studying that but here at Stanford?

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: The third thing is there's a broader category of what people might refer to as existential risk. Nuclear weapons and the salience of nuclear weapons are back with a vengeance. For the first time, we're entering a world in which there are not two but three nuclear peers as China quadruples its nuclear arsenal. India and Pakistan are at loggerheads. They both have nuclear weapons. Israel and Iran are at loggerheads over Iran's quest for nuclear weapons. North Korea is expanding its arsenal. And arms control is breaking down.

So we know that the nuclear age is back with a vengeance. Simultaneously, we're facing the climate crisis. We all lived through COVID. It won't be the last pandemic, unfortunately, I think, in our lifetimes. There are other biosecurity risks emanating from emerging technologies. And then there's also the possibility that technologies like AI will produce their own existential externalities in the form of things like rogue super intelligence or other things.

So we should be studying those things. And then lastly, I think we have to be studying the future of global democracy because democracy is under siege around the world from revisionist authoritarian powers like Russia and China. But it's also eroding in many traditional democracies that are becoming increasingly illiberal.

And advanced democracies no longer agree on what democracy is. A big divide between the United States and Europe at the moment is both laying claim to being democratic, but in fundamentally different ways.

And so the point just is, we have 150 researchers at FSI, 50 of them are tenured faculty, many of them were working at the intersection of these issues. I want to support that and I also want them to do more together.

McFaul: That sounds fantastic. That is the agenda for our moment. And I think you're right that we have some people that work on some of those things, but we have holes to fill. And I wish you success in doing that to compliment what we have here, but also to try to get these different scholars that work on these different pieces to understand how they are intertwined, right?

The future of global democracy is also highly impactful on geopolitics and vice versa. I think that is a great agenda for FSI for the future.

I mean, on my own piece: I would just say in terms of what I want to work on, I have a lot of interests, but the main research one is I just did finish this book, as listeners will know, called Autocrats vs. Democrats, China, Russia . . .

Kahl: Available now!

McFaul: Available now! Available while you're listening on your phone. You can get it, and it's highly discounted now. And I'm going to tell you a little story about that actually, Colin. I don't think we've talked about it. The original title was ‘American Renewal.’ That was like two or three years ago. Then it switched the title to ‘Autocrats vs. Democrats.’ But the subtitle, until just a few months ago was ‘China, Russia and the New Global Order.’ The now title is ‘China, Russia, America and the New Global Disorder,’ reflecting a year ago what I thought was going to be a pretty tumultuous time. And I think I underestimated how tumultuous it is and your agenda is addressing that.

But I would say two things that I want to do here at FSI. One is, when I was working on this book, I knew a lot about the Cold War, so there's a debate, are we in the Cold War or not? And I addressed that. My answer is yes and no.

But I knew a lot about the Cold War. I know quite a bit about Russia. I know a fair bit about America and America's place in the world, both from teaching and being in the government. But I had to learn a lot about China. And I've been going to China for three decades, but I'm not an expert. It took me a long time. That's why it took me eight years to finish this book

But there were two big gaps that I saw at the end of it. One is we have a lot of great people working on capabilities of these various great powers. We have a really great literature on intentions of America, Russia, and China. And big debates, by the way, on the intentions, especially on the China side. I would say comparing the debate in the Russia field to China field, there's a lot more consensus in the Russia field about intentions of Putin's Russia than there is of Xi's China, and that's a good thing. I think that debate is unsettled and we should keep interrogating our hypotheses.

But what I was really struck by is very little examination. And with some exceptions, I'm looking at my shelf. There's some really great books. But there's not that many books that look at impact of this competition on other countries in the world. And when you do find great books—there's a great one on China and Zambia, for instance—it's just China and its impact on Zambia. There's no Europe in that story. There's no Russia in that story. There's no America in that story. So that's the academic kind of research project that I want to do here with Liz Economy from the Hoover Institution, Jim Goldgeier—he's going to cover the European part. And that'll take many, many years because we want to really get into the nitty gritty of these countries. And we want to find country experts to be the main people that write that.

The second part in my book—you know, my book looks at the debate, examines where we're at, and then has these three prescriptive chapters. And even had Vice President Harris won the election last year, the structural things that you identified would have been still a part of our trying to figure out where we're going and the debate about international order and how to manage the decline of democracy, technology and the global order, that would all been there. But to your other point you made earlier, it's been accelerated by President Trump.

And in my public policy life, I want to keep engaging that debate because yes, the old order is broken. We're not going to go back to it. But the idea that we have to just go back to some Hobbesian jungle that Trump seems to want to fight in, I don't accept that as an inevitable consequence. And even if it is analytically, and I'm wrong about that, I want to do everything I can to avoid it, even if it's going to be in failure. In a way, Trump has moved us in a different direction and I want to be part of that debate.

And one of the things I would add to that is part of the reason liberal internationalists like myself have lost that debate is because we lost the American people on it. And we didn't focus enough on trying to explain why being a NATO is in our interest or explain why it's better off to have a foot in even something like the United Nations than to pull out. Why we're better off to support ideas of democracy and freedom rather than just think that it's just all about power.

And so I'm going to be spending a lot of time speaking, not just in Silicon Valley—I'm still doing that—and not just Washington and New York or Brussels and Beijing, but my next stop for my book tour is Boise, Idaho. And I've done this for a while and not everybody agrees with me. I even had a few people walk out before I even said a word because they saw that I'd worked for Barack Obama.

But what I can tell you and report is people are curious. All my talks are sold out. And the agenda you just outlined, Colin, is an agenda I think that when we have things to say with our scholars, we should bring those ideas through things like World Class. I think there's a demand and a thirst for trying to figure out this new world order/disorder that we're in, and FSI has a great role to play in that.

Kahl: Hard agree. And also I'm thrilled that this is going to be so much of your focus.

I would just say on the alliance piece: my view is that as the distribution of power changes, it's clearer than ever that foreign policy is a team sport.

McFaul: Yes.

Kahl: I used to make this reference: Michael Jordan, probably the best basketball player who ever lived. Although I'm sure there are people who claim it's LeBron or Kobe or somebody else. But if you believe that Michael Jordan was the best basketball player who ever lived, he still needed four other Bulls to win championships.

And as we go around, and address every problem that I've ever encountered as a policymaker, whether it's the rise of the Islamic state or the invasion of Ukraine, we need our team.

McFaul: Exactly.

Kahl: And our allies and partners are our team. So I think we have to tell that story. We also, as we enter this new world, have to figure out a way to re-anchor our alliances in a way that are politically sustainable on all sides, and that actually deliver benefits for the American people.

So it's not just telling a better story. There's an interesting example of this. Recently the Trump administration agreed to help South Korea with their submarine program. But South Korea in exchange is making tens of billions of dollars of investments in American shipyards . . .

McFaul: Right.

Kahl: . . . to build up our capacity. And I do think these ideas about joint industrial capacity across the free world might be a way to generate jobs, to generate political incentives on all sides to keep those alliances intact and give some people confidence on both sides of our alliances that we're not going to have these violent swings every four to eight years.

McFaul: I could not agree more. And that example you gave is a great example. And we have to be more creative about re-anchoring and win-win for everybody. I think that's a great idea.

Colin, I'm going to hand this over to you. We've already gone longer than we should have because you're so interesting. Tell us a few of the guests you have coming up on World Class.

Kahl: First of all, not only big shoes to fill on the FSI director position, but big shoes to fill as the host of World Class. We're going to try to start off with a bang in the near future. So stay tuned. We hope to have a great conversation involving H.R. McMaster, who is at Hoover, but as many of your listeners will know, was President Trump's national security adviser at the beginning of the first Trump administration.

And we're going to pair H.R. with Jake Sullivan, who was Joe Biden's national security advisor.

McFaul: Wow! Both on the same show?

Kahl: On the same show!

McFaul: Oh my God, that's fantastic!

Kahl: And the idea is to ask two of the smartest minds on different parts of the political spectrum to help get us smarter about the state of the world and where things are going for the rest of 2026. I have to say for the rest of 2026, because like we're not even a month in and we had Venezuela and Greenland and Iran, and Iran could come back and like, we're three weeks in.

But people should stay tuned because that's going to be an awesome conversation.

And then without naming names, I'm very hopeful to bring on leaders from the tech community here in Silicon Valley to interface with our scholars about some of these technology trends we talked about earlier.

McFaul: Great, excellent.

Kahl: So it's gonna be great. If you're a geopolitical nerd, you're going to love it. If you're into technology, you're going love it. And we're gonna find ways I think to both highlight the extraordinary work being done here at Stanford, but also Stanford's role in the broader ecosystem. It’s going to be fun.

McFaul: Sounds exciting, Colin. Well, first of all, thank you for taking on the role of leading FSI. We need you because of all the things you just described. Second, thanks for taking on World Class. And third, just with that teaser, I know that World Class is going to get a lot more interesting in the weeks and months to come. So congratulations.

Kahl: Thanks, Mike.

McFaul: You've been listening to World Class from the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. If you like what you're hearing, please leave us review and be sure to subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts to stay tuned, to stay up to date on what's happening in the world and why.

And for the last time, this is Michael McFaul signing off as your host of World Class. Stay tuned for the next episode hosted by Colin Kahl.