Motivation & Summary

Social, political, and religious polarization has steadily grown in many longstanding democracies. Some elected representatives and voters have come to view their opponents as illegitimate participants in politics who pose an existential threat to the nation-state; this justifies ignoring or violating democratic norms and procedures to prevent them from gaining power. As polarization increases, voters may prefer to support authoritarian parties that are viewed as better expressing their group identities, as opposed to democratic parties seen as hostile to those identities.

Trust lies at the root of these processes: polarized individuals tend to believe that those who differ from them will not act from a place of goodwill and will lack the incentive to promote their interests. Revitalizing democracy would thus seem to require revitalizing trust. Yet one’s sense of trust is often shaped by factors that are difficult to change, such as childhood socialization. How, then, can trust be increased?

In “Financial market exposure increases generalized trust,” Saumitra Jha, Moses Shayo, and Chagai M. Weiss provide evidence from an experiment conducted among Israelis in 2015. The authors find that individuals who participated in the stock market were more likely to agree with the statement that “most people can be trusted.”

Their argument builds on the intuition that stock markets are fundamentally about trust: investors take a risk by placing their assets in the hands of unfamiliar people who nonetheless have an incentive to promote their interests. As these assets grow, participants ought to become more trusting, not only of financial markets but also of people more generally. Surprisingly, the authors find that even those whose assets did not grow became more trusting. Another surprise is that the increases in trust were higher for Israelis on the political left and right. In other words, polarized voters — those who especially struggle to trust others — exhibited greater increases in trust than centrists.

Prior Research

Social scientists have analyzed trust as both a cause and a consequence. Much of this research concerns the economy, as transactions, contracts, and negotiations all require the belief that other parties will honor their commitments. Higher levels of trust may be a cause of higher economic growth. Conversely, consumers tend to distrust firms that are subject to scandals, leading the corresponding value of those stocks to decrease.

Apart from the economy, trust is also a central aspect of ‘social capital,’ which consists of the resources gained from one’s social networks. Trust can also promote good governance by enabling collective action and by providing legitimacy to political institutions. And as Americans and others learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, trust is central to public health compliance.

Survey research has identified a persistent trust deficit; less than a quarter of respondents to the World Values Survey agree with the statement that “most people can be trusted.” This deficit has many root causes. At the personal and psychological level, one’s sense of trust likely develops in childhood. Meanwhile, people who have experienced trauma or discrimination are less likely to trust others. Whether or not two people are from the same country or the same ethnic or religious group also affects their sense of trust. Those whose ancestors were victims of the African slave trade centuries ago exhibit lower levels of trust today. People in economically unequal societies are also less likely to trust each other. All of this suggests that improving trust is very difficult, especially in polarized societies.

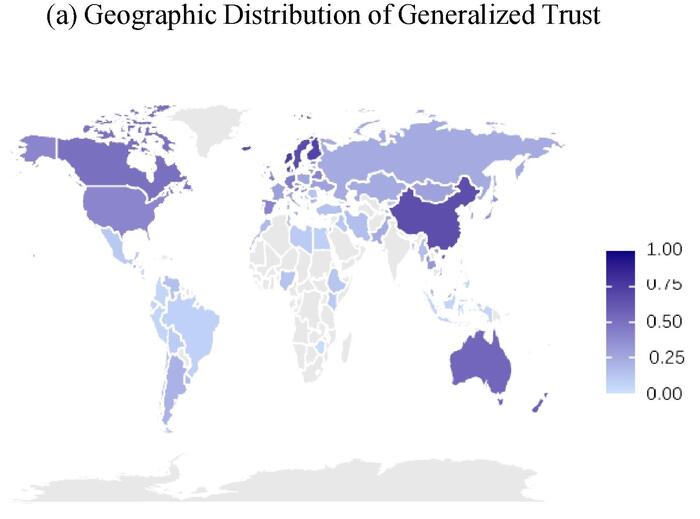

Fig. 1. Generalized trust around the world. (a) Geographic Distribution of Generalized Trust. This figure reports cross-national patterns of generalized trust from the World Values Survey (Wave 7). For each country, we report the share of respondents who state that most people can be trusted. Since Israel is not included in the most recent wave of the World Value Survey, the figure shows generalized trust data from the 2004 World Value Survey.

The Experiment

Studying whether stock market participation affects trust is difficult because participation is itself correlated with pre-existing levels of trust, as well as with other relevant factors like gender or personality traits (such as excitability). The authors’ experimental methodology seeks to overcome this by randomly allocating a large number of participants (over 1300) into treatment and control groups. Prior to this allocation, the authors conducted a survey to establish participants’ baseline levels of trust.

Those in the treatment group participated in an additional survey that explained the study rules as well as how their asset values would be determined on the stock market, quizzing them on these topics afterwards. Participants were given either $50 or $100 (USD), which was between 64% and 128% of the average Israeli daily wage in 2015.

Stock market participants received weekly updates on the prices of their assigned assets, along with a description and valuation of their portfolio, when the markets closed at the end of each week. Individuals in the treatment group were given weekly opportunities to decide whether to buy up to 10% of their portfolio, sell up to 10% of it, or make no change. (If no decision was made, they lost the 10% that could have been traded.) Participants ultimately traded at high levels: around 70% did so at every opportunity, and 80% did so in six out of the seven weeks.

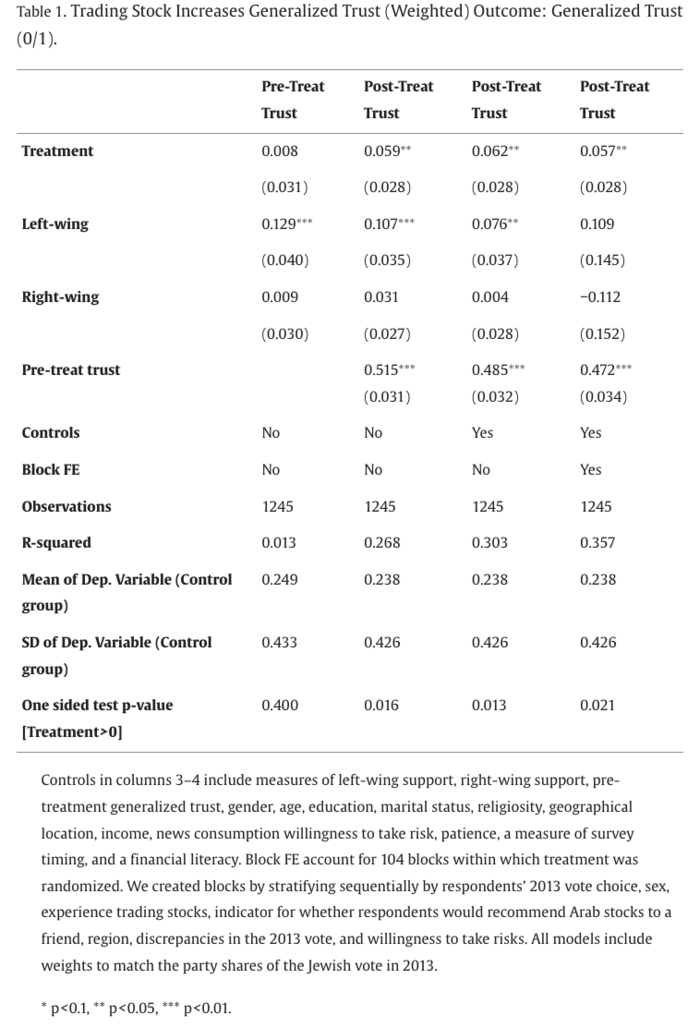

As stated above, participation increased the probability of expressing trust by around six percentage points. These effects were largest for polarized voters and for those whose stocks performed well; however, even those who suffered market losses exhibited increases in trust.

The authors carefully show how trust can be not only a cause but a consequence of stock market participation. Their approach is not paternalistic because it lets participants make independent financial decisions — as opposed to lecturing them — from which trusting attitudes then develop. In addition, the study can be replicated on a large scale because (a) it can be integrated within existing government cash aid programs and (b) participants would not need much special teaching or supervision. The authors’ approach should appeal to both those who seek solutions that promote equality and empowerment and to those who oppose top-down social programs but support market-driven solutions.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.