Meet Our Researchers: Dr. Claire Adida

The "Meet Our Researchers" series showcases the incredible scholars at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL). Through engaging interviews conducted by our undergraduate research assistants, we explore the journeys, passions, and insights of CDDRL’s faculty and researchers.

Claire Adida is a Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), a Professor (by courtesy) of Political Science, and Faculty Co-Director of the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford. Her research uses quantitative and field methods to investigate what weakens and strengthens social cohesion.

What is the most exciting or impactful finding from your research, and why do you think it matters for democracy, development, or the rule of law?

One of the most exciting findings from my work, and also from others in the field, is the role of empathy and perspective-taking in reducing prejudice and increasing inclusion. In one experiment during the height of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2016, we asked people to put themselves in the shoes of a refugee. We asked questions like, “What would you take with you? Where would you go?” When people engaged in that exercise, they became more open to refugees and more supportive of inclusion. And that was true across the political spectrum; Democrats and Republicans alike all showed greater openness after engaging in perspective-taking.

There is something really powerful about empathy. Other studies have shown the same pattern: when people imagine the perspective of someone different from them, whether it’s a refugee, a trans person, or an undocumented migrant, they become more understanding. It’s a simple but profound mechanism for building social cohesion.

How can empathy and perspective-taking be implemented on a larger scale, and how can they be used to address the challenges we see in the world today?

Well, this isn’t something you can legislate. You can’t tell politicians to force people to imagine someone else’s life. The real audience for this work is advocacy organizations like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the International Rescue Committee (IRC), because they’re already doing it. They use storytelling and humanizing narratives in their campaigns all the time.

It’s really hard, though, because we’re living in what people call the attention economy, which is driven by social media. Everything is about visibility, clicks, and headlines, and there’s always a new crisis. It becomes difficult for people to hold on to empathy for more than a moment because the focus is constantly shifting from one story to another. Even if a big influencer were to advocate for refugees or displaced communities, another could just as easily come along and dehumanize them or spread misinformation that undermines this. So it becomes this constant tug-of-war between empathy and fear, between humanizing and othering.

With that being said, I think social media can also be used as a really powerful tool for sharing stories and reaching people who might not otherwise engage with these issues. It gives us a space to humanize experiences and make them visible at a scale that wasn’t possible before. The challenge is figuring out how to use these platforms not just to get attention for a moment, but to actually build connection and understanding that last beyond a single news cycle.

How does this translate into policy?

Ultimately, I do think that public opinion matters for policy. The way people feel about migration or refugees — whether they see them as part of the community or as outsiders — shapes which policies are politically possible. And today, public opinion is shaped more than ever by social media. It’s not just voters who are influenced by online narratives; policymakers and donors are too. That’s why empathy and communication are central to policymaking, as social media now plays such a major role in shaping how both the public and those in power think and respond.

Can you tell me more about your work at the Immigration Policy Lab?

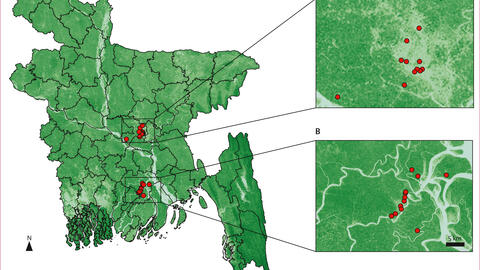

I just joined as Faculty Co-Director and am currently leading two key projects focused on migration and development, particularly in the Global South.

One major area is climate migration, understanding how environmental shocks affect migration decisions. The people most vulnerable to climate change are often the poorest. We’re trying to understand how they perceive risk, what strategies they use to survive, and when migration becomes an option. We’re currently raising funds to collect data in places like Colombia and rural Guatemala.

Another big project focuses on return migration, looking at people who have been expelled or deported, as well as those who self-deport. We’re building partnerships with organizations like Mercy Corps and the IRC to study how they reintegrate, what challenges they face, and whether existing programs are actually helping.

What have been some of the most challenging aspects of conducting research in this field, and how did you overcome them?

I would say interest and funding. Studying migrant integration is not popular these days; it feels like everyone is obsessed with AI or how technology can solve problems. That also creates challenges with funding and resources, especially from federal sources, because projects like ours require long-term fieldwork and collaboration, which are expensive and time-intensive.

That said, I’ve been really fortunate to find a strong community and support system here at Stanford and at CDDRL. Being part of this environment has enabled me to connect with others who care about these issues and to find the resources needed to keep the work going.

What gaps still need to be addressed in this research, and what do you hope to study in the future?

I think a big gap that hasn’t been studied enough is who actually engages with empathy-based initiatives in the first place. We know that when people are asked to imagine themselves in someone else’s shoes, they become more open and inclusive. But who is voluntarily clicking on those websites or reading those stories? Probably people who already care. That’s a limitation, because it means we might just be reinforcing empathy among those who already have it.

What I’d love to study next is how to reach people who don’t. People who avoid these stories or who hold more exclusionary views. What kinds of messages or media could reach them? Could framing, visuals, or certain messengers make a difference? Understanding that is crucial for figuring out how to scale empathy beyond its existing audiences.

If you had to give one piece of advice to students who want to get involved in this kind of research, what would it be?

Take my class next quarter! We talk about all sorts of issues related to migration and inclusion. But seriously, get involved early. Try to work as a research assistant, even on small projects. That’s how I got started, by working under a professor who brought me into areas and questions I didn’t think I’d be interested in. Those experiences can completely change your perspective and open doors you didn’t even know existed.

Lastly, what book would you recommend for students interested in a research career in your field?

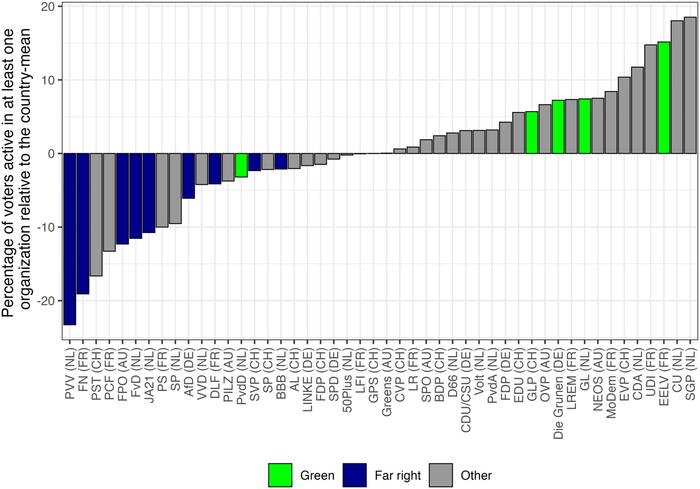

I’ve heard very good things about The Truth About Immigration by Zeke Hernandez, which is more from an economist’s perspective, and I love Rafaela Dancygier’s Dilemmas of Inclusion, which looks at the challenges left-wing parties face in Europe. They’re the parties of inclusion, but they also have to navigate tensions when the groups they’re including hold more conservative social values. It’s a really interesting read for understanding how inclusion plays out in democratic politics.

Adida’s work highlights how understanding the human side of migration through empathy and perspective-taking can lead to more inclusive policies and stronger communities worldwide.

Read More

Exploring how empathy and perspective-taking shape migration, inclusion, and public attitudes toward diversity with FSI Senior Fellow Claire Adida.

FSI researchers work to understand continuity and change in societies as they confront their problems and opportunities. This includes the implications of

FSI researchers work to understand continuity and change in societies as they confront their problems and opportunities. This includes the implications of