Foreign Aid and the Performance of Bureaucrats

Foreign Aid and the Performance of Bureaucrats

CDDRL postdoctoral scholar Maria Nagawa examines how foreign aid projects influence bureaucrats’ incentives, effort, and the capacity of bureaucratic institutions.

Although the impact of foreign aid on governance and development has been widely debated, its effect on bureaucracies remains underexplored. This is significant as bureaucracies play a vital role in key functions of the state and can affect development and growth. CDDRL postdoctoral scholar Maria Nagawa addressed this gap in a recent research seminar examining how project aid impacts the incentives and efforts of bureaucrats in aid-receiving countries.

Aid projects have predetermined objectives, activities, timelines, and budgets that rely heavily on bureaucrats for implementation. Consequently, they can lead to a reallocation of bureaucrats’ time and effort away from core government duties. To explore these dynamics, it is important to consider bureaucrats’ preferences for work and how they allocate effort. In the context of aid, these preferences can relate to specific projects and organizational characteristics. Project preferences may include financial incentives, ownership over priorities, and discretion in implementation, while organizational preferences include exposure to donor funding, pay inequities, and coordination with peers. With these factors in mind, Nagawa conducted her study in Uganda, one of the top foreign aid recipients in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The study takes a mixed-methods approach, utilizing interviews, surveys, and survey experiments. Because data on bureaucrats who work on aid projects is virtually non-existent, primary data collection was vital to generating evidence on how aid reshapes bureaucracies. Nagawa conducted 64 semi-structured interviews across 14 central government ministries and agencies, finding that although bureaucrats are pro-socially motivated when they join government, donor-funded projects amplify the importance of financial incentives. These projects provide attractive allowances and other benefits, and while such rewards can drive bureaucrats’ effort on projects, they also create tensions among colleagues to the point of eroding collaboration within departments. This is in part because projects are selectively allocated under unclear criteria. Bureaucrats also highlighted how donor priorities often took precedence, making it harder for them to advance contextually appropriate policies.

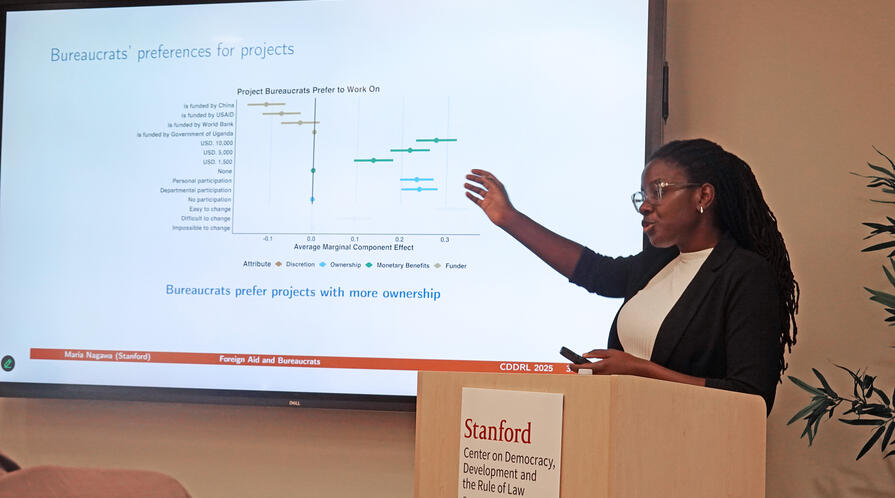

Results from the survey of 559 mid-level bureaucrats across six ministries reinforced these findings. Nearly 70 percent of bureaucrats had worked on aid projects, and many observed that such projects increased inequalities in pay and opportunity within ministries. To further explore these dynamics, Nagawa conducted conjoint survey experiments, which confirmed that monetary gain was the strongest driver of effort on projects. Although bureaucrats had strong preferences for ownership and discretion, these factors did not influence their willingness to increase effort on projects.

Nagawa’s findings highlight how aid projects reshape bureaucrats’ incentives in ways that can negatively impact state capacity. Many civil servants value government service and prefer the autonomy of government funding, but the structure of project aid often pushes them to prioritize donor-funded projects over their governmental duties. This weakens the internal cohesion and collaboration necessary to maintain a robust government.

Nagawa underscored the need for increased donor coordination to reduce bureaucratic burden, alignment of aid with the budget cycle to ensure synergy between aid projects and government work, and focusing funding on scaling local priorities. The findings from this research provide an important roadmap for how to reform aid delivery and ensure aid supports rather than undermines government effectiveness as international development assistance undergoes unprecedented changes.